An litir dhearg

Bí ar an eolas! Faigh ár nuachtlitir le bheith suas chun dáta leis na feachtais ar fad.

Daithí Mac Gabhann and his parents Mairtín and Seph have led the Donate4Daithí organ donation campaign in recent years. Their campaign to give ‘the gift of life’ was a very successful one as from 1 June 2023 the law around organ donation will change to an opt-out system.

The new law will be known as ‘Dáithí’s Law’ in recognition of the brave young man who has been on the waiting list for a heart transplant since 2018. Just a few weeks ago, and as I write this article on the intimidation faced by Irish speakers, I was informed by the family that they received a two page, hate filled, sectarian, handwritten letter to their home all because they’re raising their son with Irish. It intended to intimidate the family and deter them from their work but the Mac Gabhann family rightly rose above it and said; Hate never wins!

The Irish language community is riding on the crest of a wave. The British Government finally introduced the Language and Identity bill at Westminster three days after 20,000 people attended the biggest ever Irish language rally in May of last year.

More than 7,000 pupils are enrolled in Irish medium education across the North; An Cailín Ciúin, an Irish language feature film, made history when it was nominated for an Oscar; the Irish language rap group Kneecap is currently amongst the most popular acts in the music scene; there is a sharp rise in demand for Irish language classes, with nearly 20 venues across Belfast offering adult classes in the language; over 500 learners attend classes in East Belfast as part of Turas, a project established a decade ago to connect people from Protestant communities to their own history and the Irish language.

In addition, census figures show a 43% increase in those who use Irish as their main language and 17% growth in overall usage amongst the wider population. The household survey shows a higher percentage of young people with Irish in comparison to the older generation. This is a young, vibrant and emerging community, not on the margins but very much part of the fabric of our society.

I would like to be telling you that the peace process was a catalyst for the growth of the Irish language but, unfortunately, that hasn’t been the case.

2023 marks the 25th Anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement. The Irish language featured strongly in the agreement, with several commitments made under the theme of rights, safeguards and equality of opportunity. It was promised that restrictions to the maintenance and development of the language would be removed.

The agreement was to mark a new era in the relationship between the Northern State and the Irish language community. I would like to be telling you that the peace process was a catalyst for the growth of the Irish language but, unfortunately, that hasn’t been the case.

Instead, the language has faced continued denigration by public representatives, including government ministers, the withdrawal of funding from established schemes aimed at promoting fluency and the dismissal of our demand for the delivery of promised language rights as a demand for ‘preferential treatment’.

The Irish language has featured in all of the major peace agreements as a result of a long history of conflict. The 14th century Statutes of Kilkenny and the 17th and 18th Century Penal Laws were key moments in the cultural colonisation of Ireland.

Such laws were a calculated attempt at cultural colonisation and they were, to a large extent, successful. Irish speakers were marginalised and excluded from public life, and were banned and prosecuted for using, educating and living through their native tongue. Despite these repressive measures, more than half the population remained Irish-speaking according to the census of 1841.

Opposition to the language is often rooted in sectarianism and such hostile opposition has had a major impact on Irish speakers and activists.

However, the Great Hunger 1845-51 and its aftermath substantially weakened Irish-speaking Ireland through death and emigration. The teaching of the Irish language and, indeed, use of the language was forbidden in the National School system established in the 1830s.

The irony in all of this is that the British Government, who have been responsible for centuries of deliberate policies to systematically suppress the language, have now legislated for the Language and Identity Bill to protect and enhance the language. That they have done so as a result of decades of tireless campaigning by Irish language activists.

Despite the significant progress made in recent years and now with the Language and Identity Bill being implemented, Irish speakers in the North of Ireland continue to experience marginalisation and exclusion.

Political opposition to the language isn’t from political parties on the margins; it comes from some of the highest political office-holders. Until recently the DUP, as the largest party in the North, consistently opposed and frustrated progress on Irish language matters. In more recent times, they attempted to prevent the Language and Identity Bill from progressing in Westminster.

Opposition to the language is often rooted in sectarianism and such hostile opposition has had a major impact on Irish speakers and activists. The DUP has withdrawn funds, introduced English-language only policies, blocked bilingual signage, frustrated the North-South political structures on language matters and continues to threaten to roll back legislation that promotes and encourages Irish medium education.

All of this is consistent with how the State has treated the language over the 100 years of its existence.

The most concerning element of political unionism’s constant public vilification and ridiculing of the language is that it has created an unprecedented climate of hostility, encouraging direct intimidation of Irish speakers and activists.

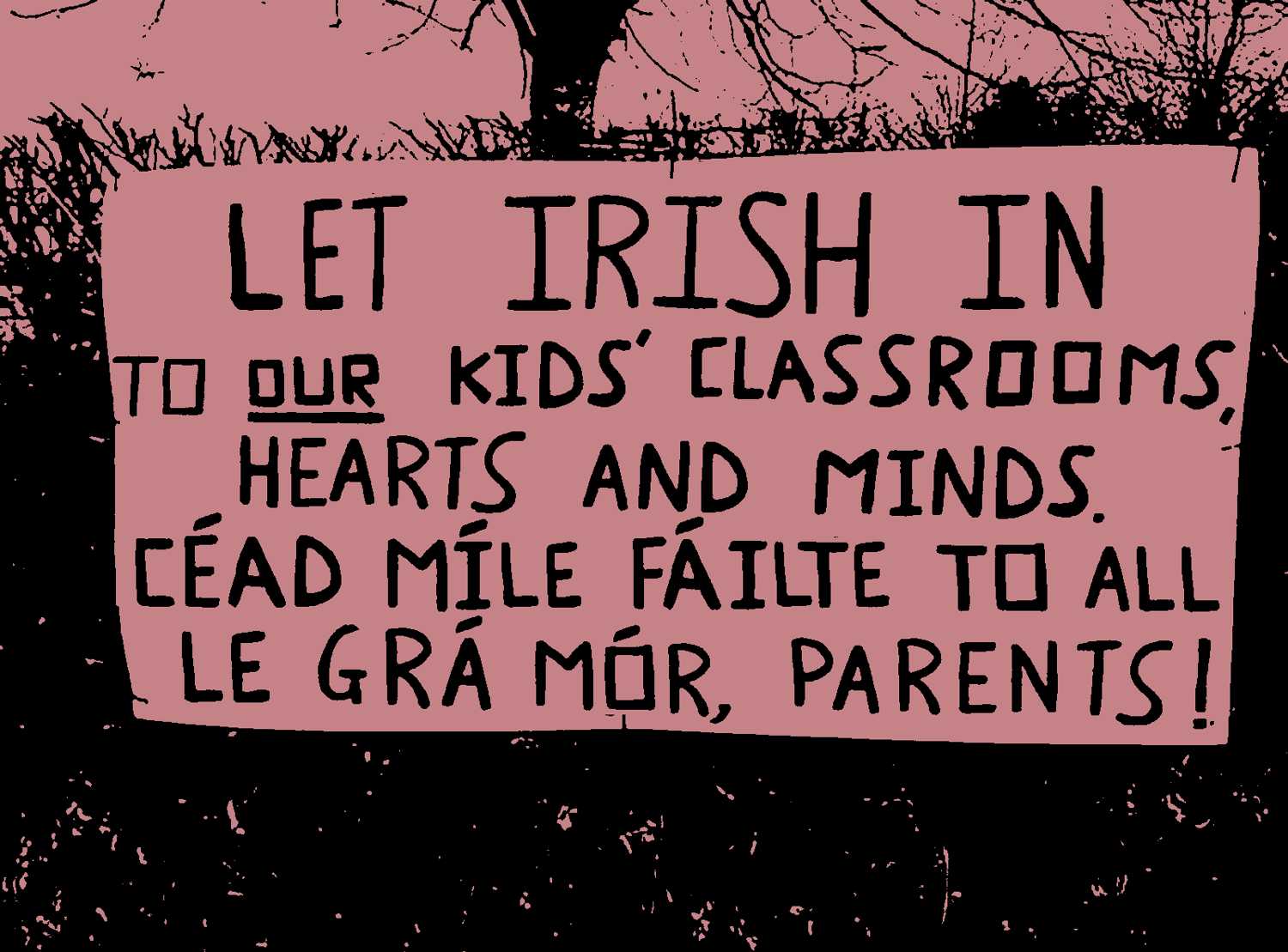

This was evidenced recently when a threatening sign was erected outside a County Down primary school warning it to ‘Keep Irish Out” . IME research has concluded that Irish-medium schools have faced “ill-disguised sectarianism and anti-Irish bias” from education authorities.

Bilingual signs have been vandalised over 300 times in the past five years with a third of those signs destroyed in the past year alone. An East Belfast Irish language pre-school, Naíscoil na Seolta was forced to relocate due to threats, while language activist Linda Ervine, who was behind the development of the pre-school, has been the victim of a social media hate campaign. Linda often talks of the veiled threats against her and the organisation Turas that she leads.

Dream Dearg activists who have campaigned for language rights have been targeted on sectarian posters and face constant harassment and sectarian abuse on social media. TG4’s children’s programming block Cúla4 has had adverts across Belfast destroyed or defaced. Graffiti was dubbed on posters with sectarian slogans, including ‘KAT’, an acronym for ‘Kill all Taigs’.

A virulent and nasty campaign of opposition to the Irish language from political parties including the DUP and TUV and their appointed government ministers has encouraged and facilitated this climate of hostility and intimidation.

25 years on from the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, it’s evident that much more needs to be done before we can truthfully say that the promise of that agreement (and, indeed, subsequent agreements) has been realised.

Discrimination against the Irish language community did not end with the signing of our peace agreement. Colonial legacies were not wiped clean by the signatures of politicians and heads of state on an international agreement. Despite the obstacles outlined above and despite the climate of hostility, threats and intimidation, the Irish-language community is growing in terms of its size, its confidence and its determination to achieve justice.

This proud and resilient community has never sought permission to ascertain its rights and demands and nor has it held back from mounting effective political opposition.

Together we will continue to grow and build this community, we will continue to insist that agreements are fully honoured and that international and domestic laws are adhered to, thereby providing the solid foundation to effectively challenge hostility, sectarianism and marginalisation.

This article was originally published as part of the Just News April 2023 series, co-ordinated by CAJ. The entire issue can be accessed here.

Bí ar an eolas! Faigh ár nuachtlitir le bheith suas chun dáta leis na feachtais ar fad.