An litir dhearg

Stay up to date! Receive a newsletter from us to keep up with the campaigns.

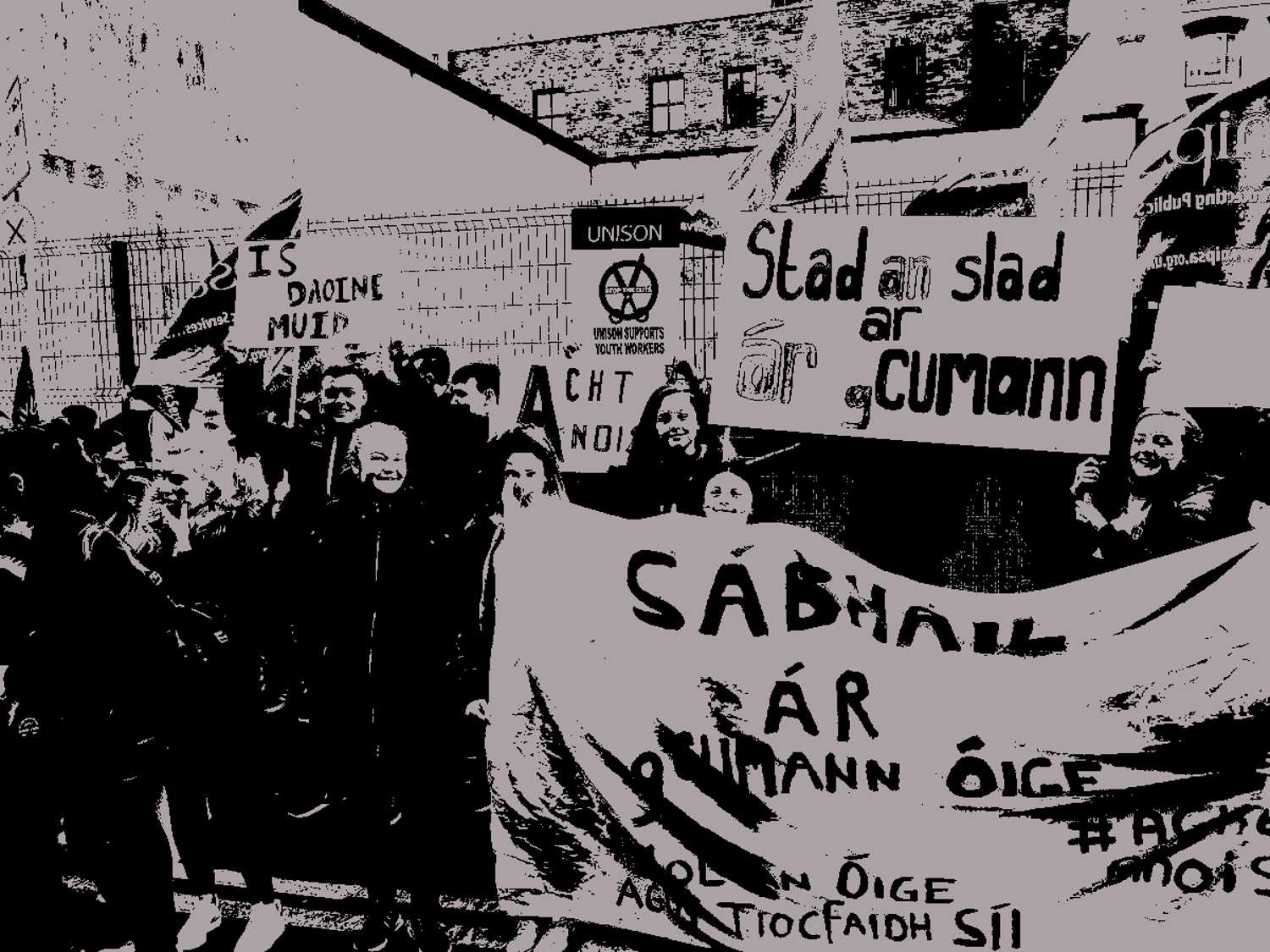

It is palpably clear from the inspiring examples repeatedly set forth by recent generations of young Irish speakers in their active and visible involvement in the campaign for language rights, that young people are at the heart of the movement for the revival of the Irish language. As the colourful crowd of almost 20,000 demonstrators and activists demanding their basic human rights approached Belfast City Hall in May 2022 as part of the third ‘Lá Dearg’ in 8 years, young Gaeilgóirí comprised a huge, visible and vocal portion of that contingent.

Thousands of the young people in attendance that day are enrolled in Irish medium nursery, primary and secondary schools whose myriad banners and emblems were on full and proud display. In full view also, were countless posters, placards and signs representing the multitude of Irish language youth clubs that have emerged over the last decade in response to the community demand for informal learning opportunities through the medium of Irish for young people.

In exploring the importance of these types of opportunities it is useful to consider the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), as it provides an international best practice and right-based framework for how all of us, in our rapidly changing and diverse societies, should engage with young people. The UNCRC is the most complete statement of children’s rights ever produced and is the most widely-ratified international human rights treaty in history.

Key to understanding how this document impacts on the lives of young Irish speakers in 2022 requires a brief exposition of some of the conventions most relevant articles. Article 29, for example, discusses the goals of education, expressing that it must,

“develop every child’s personality, talents and abilities to the full, and must encourage the child’s respect for human rights, as well as respect for their parents, their own and other cultures, and the environment.”

Article 30 focuses on the rights of young people from minority or indigenous groups, positing that,

“every child has the right to learn and use the language, customs and religion of their family, whether or not these are shared by the majority of the people in the country where they live.”

Finally, Article 31, the right of children and young people to enjoy leisure, play and culture, explicitly states that every child has,

“the right to relax, play and take part in a wide range of cultural and artistic activities.”

Traditional forms of mainstream pedagogy tend to address these goals through the traps of formal education, which is often limited by the constraints of practice orthodoxy, formal educational policy, underfunding, and the nature of the educational ‘banking’ process (see Paolo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed) – which engenders passivity in recipients of prescribed formal curricula.

The informal approach of youth work, on the other hand, although limited in this case by an inadequate state policy for Irish medium (IM) youth work, views education and learning from a more participatory, democratic, and critical perspective. This approach uses voluntary informal relationship building to encourage dialogue among and between young people, peers, and adults, who are treated as equals and co-creators in the learning process.

This community-led and youth-centred revival in education has manifested in the emergence of dozens of local Irish language youth services which have flourished over the past decade or so, bringing opportunities for personal, social, political and linguistic development to thousands of young people across the youth sector. In the late nineties, volunteers and activists from the Upper Springfield’s Irish language community in West Belfast organised ‘An Chlub Eachtra’, providing informal services for young people through Irish, but since the establishment of the first Irish Medium youth sector clubs between 2009-2012, the sector has undergone a fascinating journey reminiscent in many ways of the Shaw’s Road Gaeltacht revival.

There are over 25 established Irish language youth work services, and membership uptake, alongside the volume of programmes and quality of service provision, has grown exponentially, mirroring on one level, the ever-increasing pupil enrolment rates in Irish Medium formal education. The existence of these services is of course a testament to the hard work, passion and sacrifices of previous generations of Irish language activists, and those continuing today recognise well, the motto, ‘Ná habair é, déan é!’. Indigenous youth work carries that ethic in its architecture. The principles and practices underpinning the Irish medium youth work taking place throughout this burgeoning sector can be articulated through the Indigenous Youth Work model and its approach – so what is Indigenous Youth Work?

Indigenous Youth Work is a unique form of youth work which incorporates traditional youth practices, and is uniquely and inherently connected to the wider project of language revitalisation and community regeneration from which Irish medium infrastructure and services have been established. Recognising Indigenous Youth Work as an indispensable pillar of this revitalisation project allows for a holistic understanding of its core purpose and its potential for the development of transformational decolonising practices.

Thousands of young Irish speakers from Irish language communities across the North are involved in Irish Language sporting clubs; cultural centres; family and arts projects; day-care centres, pre-schools, nurseries, primary and secondary schools, and further education; community-based projects; radio and media projects; and grassroots language rights campaigns, in which Irish is the dominant acoustic of those driving these initiatives.

This social context helps to facilitate the participation of young Irish speakers in the Indigenous Youth Work model, which is currently being administered throughout the Irish medium youth sector. At the same time, Indigenous Youth Work has become a catalyst and platform for activists and young leaders who have and will continue to contribute to the regeneration project in the years ahead. However, obvious barriers to the development of this work exist, most notably outside of Belfast, where provision is affected by rural isolation and lack of investment in frontline resources (i.e. funding, facilities, adequate training and resources, and social opportunities for young people).

To explore the barriers and opportunities this work presents, Fóram na nÓg, the regional body representing Irish medium youth work, carried out research in 2021, aimed at identifying gaps in participation, and barriers to implementation of the initial and preceding Irish Medium Youth Work model (Glór na Móna, 2015). The research sought also to examine the advantages and positive impact of IM youth work in the Irish language community, to identify lessons for the wider youth sector and other minority language youth movements, and to suggest how IM youth work could inform the emerging youth policy framework in the North. The research report and its subsequent recommendations led to the development of the Indigenous Youth Work model, which in one sense consolidates the vital youth work practice that has been ongoing since the establishment of the IM youth sector.

Indigenous Youth Work, therefore, places a particular emphasis on the core component of the youth work process - the building of positive relationships. The model encourages the development of opportunities for young people to build relationships and friendships through the medium of Irish, while also developing a crucial understanding of what healthy and positive relationships look like with adults and other older peers. The indigenous Youth Work model, in providing opportunities for young people to develop a deeper connection with, and understanding of, the Irish language, promotes and fosters the social usage of the Irish language within the delivery of all of its services.

This informal approach to language, relationship building, and learning, encourages the use of Irish as the primary means of communication, or dominant acoustic, within indigenous youth work spaces. This non punitive approach to language development serves to normalise the voluntary and social use of Irish for young people, creating immersive sociolinguistic environments which foster a strong sense of community, identity and linguistic self-confidence. The strong sense of identity is further enhanced in the wider experiences of young people, as Irish language youth clubs almost exclusively develop alongside, draw upon, and collaborate with, local IM schools and grassroots community development organisations.

The awareness developed among young people of the interconnectedness of the Irish Language community and their vital place within it, serves to further empower young people, with many of them becoming involved in political activism in a local, national and international context. The important emphasis placed by the indigenous Youth Work model on critical thinking, enables young people to develop advocacy skills and grassroots community empowerment practices. Such practices form a basis for youth-led activism that leads to the strong sense of ownership young people have over their youth clubs.

In the context of the abundant barriers facing young Irish speakers, the indigenous Youth Work model recognises the need for young people to advocate for immersive Irish Language youth spaces. The active participation of young people in securing their own services encourages feelings of acceptance and common identity among young Gaeilgóirí, which, in a regenerative way, further fosters the sense of ownership they have over their youth clubs.

Looking ahead, opportunities for development seem abundant while significant barriers to progress also remain, notably the absence of adequate frontline funding and resources that guarantee IM youth clubs can keep their doors open throughout 2023 and beyond. Likewise, the continued growth of IM youth work necessitates the need for a bespoke state funded ‘Irish medium youth work scheme’ that both recognises the unique nature of Irish language youth work and allows for the evidence based incremental growth of IM youth services.

It is also worth considering that the current youth work framework administered by the state throughout the North was created 25 years ago, over a decade before the establishment of the Irish language youth work sector. The framework ‘A Model for Effective Practice’ (1997) falls short of addressing all the elements inherent in the Indigenous Youth Work approach, and therefore, is somewhat inadequate in terms of addressing the needs of young Irish speakers, as outlined in the UNCRC and in other relevant pieces of research. Against this backdrop, the Irish language youth sector continues to endure and progress, working hard alongside partners, innovating and developing informal and immersive sociolinguistic opportunities that give young people a real chance to shape their own educational experiences, to think critically about the worlds they inhabit, and most importantly, to have fun while living their lives trí Gaeilge.

Stay up to date! Receive a newsletter from us to keep up with the campaigns.